La centralità della componente ritmica

Written in Italian by Franco Buffoni

| A specimen of Babel: Stories on the loss of the earth’s one speech and the confusion of languages

Una poesia originale non è una poesia che parli di cose di cui nessuno abbia mai parlato prima. Leopardi è unico quando parla della/alla luna, non perché l’oggetto sia originale (lo troviamo persino nelle lettere che il Colletta gli scrive), ma perché la sua poetica è immensamente pulsante e vitale. Keats – quando nel distico conclusivo dell’Ode on Grecian Urn associa Beauty a Truth e Truth a Beauty – non compie un’associazione originale: sono due termini che l’estetica inglese del Settecento frequentemente pone in connessione. Ma Keats rivive febbrilmente quell’associazione all’interno della sua poetica. E quei versi, letti una volta, non si dimenticano.

Questo avviene perché la poesia è un linguaggio: un linguaggio diverso da quello che usiamo per comunicare nella vita quotidiana e di gran lunga più ricco, più completo, più compiutamente umano. “Un linguaggio”, come scrive Giovanni Raboni, “al tempo stesso accuratamente premeditato e profondamente involontario, capace di connettere fra loro le cose che si vedono e quelle che non si vedono, di mettere in relazione ciò che sappiamo con ciò che non sappiamo”.

Ho molto tradotto nella mia vita e sono andato sempre più convincendomi che la vera differenza non sia tra prosa e poesia, ma tra una scrittura provvista di un proprio ritmo interno e una scrittura che tale ritmo non lo possiede.

Lo sosteneva già Beda il Venerabile con la chiarissima distinzione: “Il ritmo può sussistere di per sé, senza metro; mentre il metro non può sussistere senza ritmo. Il metro è un canto costretto da una certa ragione; il ritmo un canto senza misure razionali”.

Una distinzione che ritroviamo modernamente espressa nel Traité du rythme di Meschonnic e Dessons: “Il ritmo non è formalista, nel senso che non è una forma vuota, un insieme schematico che si tratterebbe di mostrare o no, secondo l’umore. Il ritmo di un testo ne è l’elemento fondamentale, perché ritmo è operare la sintesi della sintassi, della prosodia e dei diversi movimenti enunciativi del testo”.

Con i poeti (ma uso il termine in senso anceschianoLuciano Anceschi, Autonomia ed eteronomia dell’arte: sviluppo e teoria di un problema estetico (Sansoni: Florence, 1936), molto ampio: meglio sarebbe scrivere “con gli artisti”) ciò che conta del ritmo è il momento in cui esso si fa parola, cioè diventa linguaggio, e dunque si realizza attraverso una particolare intonazione. (In quanto il ritmo è soggetto, se un poeta trova il ritmo, trova il soggetto; se non lo trova, i versi che sta scrivendo non sono arte).

Il ritmo è dunque questo respiro interno alla scrittura, che ingloba tutte le metriche. Perché le metriche sono un fatto storico, possono mutare, fondamentalmente sono legate alla moda, nel senso leopardiano del termine. Mentre il ritmo è ancestrale: è quel respiro che viene dall’imparare a parlare, dal battito del cuore materno.

Certamente non a caso Meschonnic, al riguardo, cita esempi sia dall’ambito letterario sia da quello delle arti figurative. In questo secondo caso, basta sostituire al termine “parola”, i termini “tratto”, “immagine” o “raffigurazione”. La differenza non è dunque tra pittura astratta e pittura figurativa, ma tra una pittura (astratta o figurativa) provvista di un proprio intrinseco ritmo, di una propria misura, e una pittura (astratta o figurativa) che invece ne è sprovvista. La seconda non è arte. Punto.

È evidente che le difficoltà di ordine traduttologico che incontro traducendo The Four Quartets appartengono alla stessa famiglia di difficoltà che incontro traducendo The Waves, anche se ad occhi ingenui T.S. Eliot ha scritto in poesia e Virginia Woolf in prosa.

Riprendendo una celebre riflessione di Bachtin sulla traduzione come rapporto dialogico tra due entità artistiche – un rapporto che diviene non più “di rango, ma di tempo” – l’opera non è immessa nel movimento del linguaggio e nella temporalità della ricezione solo nella lingua d’arrivo, ma anche nella lingua di partenza. Questo incontro-scontro scava una differenza e quindi rinnova anche l’opera di partenza.

In sintesi, potremmo prendere le mosse dalla questione della ritraduzione: perché diamo per accettato che sia “lecito” ritradurre? Perché riteniamo che ogni generazione voglia avere il proprio Goethe, il proprio Dante, il proprio Shakespeare in grado di parlare nella lingua letteraria di quella generazione. Io ho tradotto Keats nel 1980, la mia traduzione è ancora in circolazione, ma sono sicuro che un altro poeta (o io stesso) tra qualche anno ritradurrà Keats in italiano e lo riproporrà. Perché diamo per scontato che questo sia “lecito”? Perché diamo per scontato che la lingua sia in movimento nel tempo, che il nostro italiano sia costantemente in trasformazione. E il passaggio che compiamo con il concetto di Sprachbewegung è volto a includere in questo movimento del linguaggio anche il testo scritto nella lingua di partenza. Quel classico antico o moderno che andiamo a tradurre si è dunque spostato anch’esso nel tempo.

Non solo “diviene” la lingua d’arrivo – cosa ovvia dal tempo di Humboldt – ma diviene anche quella di partenza, perché nei decenni, nei secoli, le strutture che compongono quel testo sono andate modificandosi: la struttura sintattica, quella grammaticale, i valori semantici, la pronuncia. Come si può pensare che quel testo sia rimasto lo stesso? E qui interviene il concetto di traduzione come incontro “poietico”, come incontro di poetiche. Se tradurre letteratura porta alla realizzazione di un incontro tra la poetica del traduttore e la poetica del tradotto, questo incontro – che avviene in un punto x del tempo e dello spazio – è unico e irripetibile, perché unico e irripetibile è lo stato delle due opere e delle due lingue che in quel momento si incontrano.

Lo stesso traduttore, a distanza anche di poco tempo, traduce in un modo diverso. È un esperimento che, tra l’altro, ho fatto con me stesso, ritraducendo Seamus Heaney senza controllare le traduzioni che avevo steso dieci anni prima. Come due frecce che si intersecano – e solo in quel preciso momento si intersecano in quel modo – avviene l’incontro poietico tra testo di partenza e testo di arrivo. In un altro momento – successivo o precedente – le due frecce (i due testi) si sarebbero intersecati in modo diverso.

Impostando la riflessione teorica in questo modo, abbiamo coniugato il concetto di movimento del linguaggio nel tempo con il concetto di poetica. Ma qui preme alle porte anche il concetto di intertestualità, per chiudere l’elenco dei cinque punti fondamentali (tutti coniugabili tra loro: poetica, ritmo, intertestualità, avantesto, movimento del linguaggio nel tempo) che permettono alla nostra riflessione di abbandonare il campo delle concezioni dicotomiche: ut orator/ut interpres; traductions des poètes/traduction des professeurs; fedele alla lettera/fedele allo spirito; e così via.

Per concludere ritornando al concetto di ritmo, allo stato attuale della ricerca si potrebbero indicare tre fondamentali indirizzi della “ritmologia”: un indirizzo filosofico, un indirizzo filologico-linguistico, e un indirizzo poetico.

Nel primo ambito configuriamo i filosofi, che tendenzialmente dovrebbero applicarsi alla categoria della ritmicità in senso ampio, cercando la funzione che il ritmo ha nel mondo.

Nel secondo ambito configuriamo i filologi, che guardano al ritmo cercando anzitutto di definire che cosa esso sia (e qui la auctoritas prima è quella di Beda il Venerabile). Compito dei filologi è dunque di accordarsi sul significato, di studiare la parola, e infine di condurre l’analisi secondo modalità che contemplano la lingua e la storia della lingua.

Con i poeti – come sì è detto – ciò che conta del ritmo è il momento in cui esso si fa parola.

Comune ai tre ambiti è la ricerca di come il ritmo metta ordine nel – e modelli il – pensiero.

Sia che si parli di ritmo letterario o di ritmo musicale o di ritmi naturali (maree, ecc.) si parte da un concetto di misura, di ripetizione, di continuità, di discontinuità, di cadenza. Battito del cuore, dunque, come l’esempio più alto di qualcosa di alieno dalla necessità che l’uomo sia nella storia, di ben più animalesco e profondo, di ineluttabile e ancestrale, come l’espansione e l’implosione dell’universo, come il respiro primordiale.

Parrebbe questa la linea di definizione preferita dai poeti. Ritmo come una vibrazione che attraversa il mondo e in varia misura il corpo umano, inteso come sonda che percepisce e recepisce onde dotate di una corporeità. Dunque, di un ritmo estraneo alla soggettività poetica, che scorre e passa nel mondo, investendo la natura e le persone.

D’altro canto, se si conviene sul fatto che la prosodia e la cadenza sono i meccanismi grazie ai quali il bambino accede al linguaggio, il poeta – nel suo poièin – non farebbe che rispecchiare questa acquisizione primaria della lingua. Secondo questa prospettiva, si nasce poeti in quanto la musica è nell’anima. E il ritmo attraversa il mondo, si traduce nel corpo e attraverso questo viene restituito al mondo: un processo che oggi può essere “disturbato” dai suoni meccanici della modernità.

In questa ottica, è evidente, viene completamente a cadere la differenza storica tra prosa e poesia. La vera differenza è tra una scrittura che possiede un proprio respiro (un proprio ritmo) e una scrittura che ne è priva. Poi, che vada a capo prima della fine della riga, o che sia scritta in una delle tante gabbie metriche che nelle varie epoche e lingue caratterizzano la scrittura poetica, diviene un dato non particolarmente rilevante.

* * *

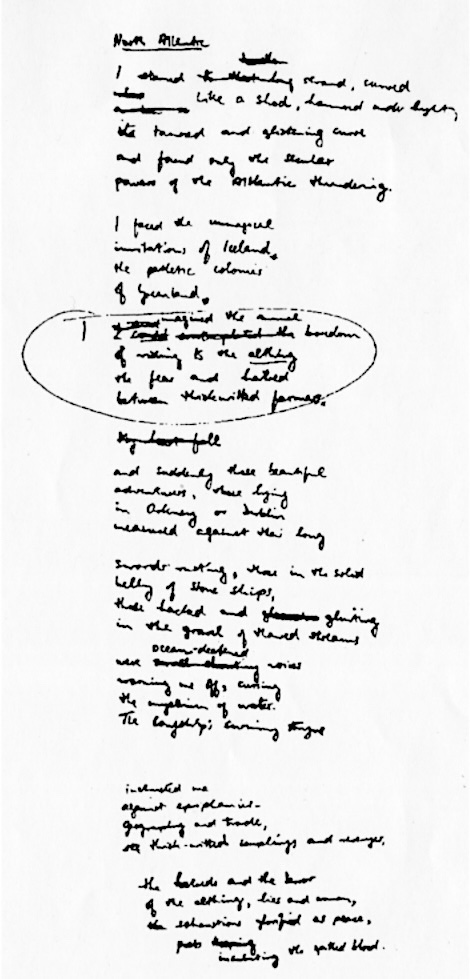

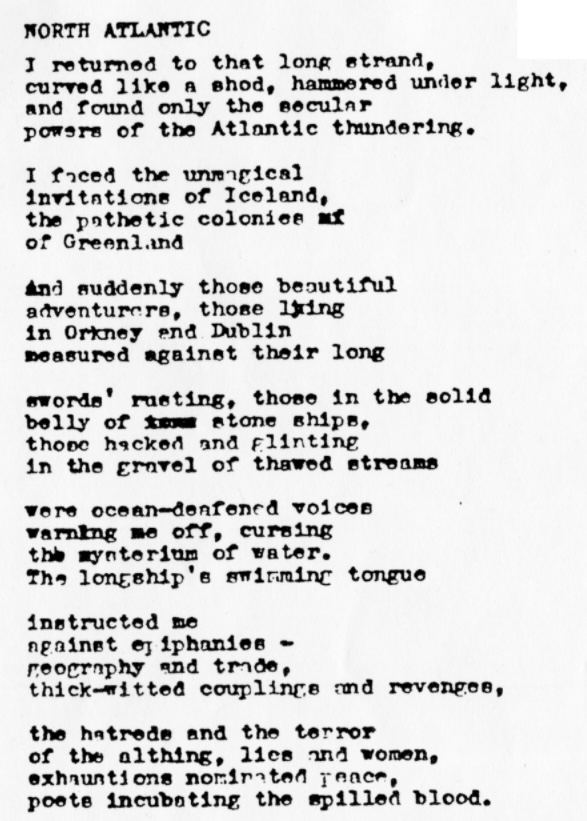

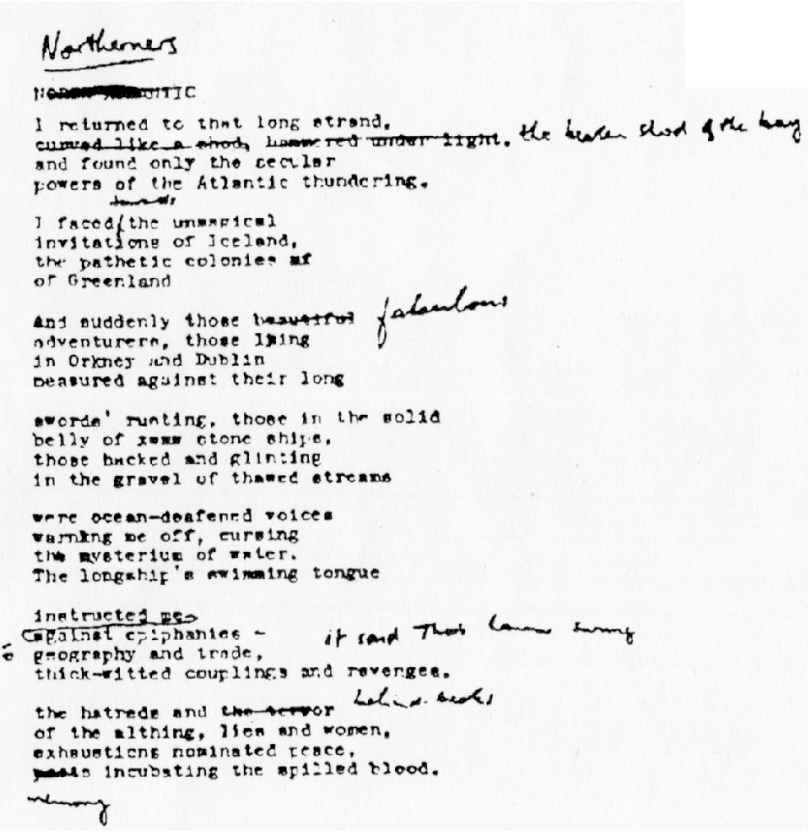

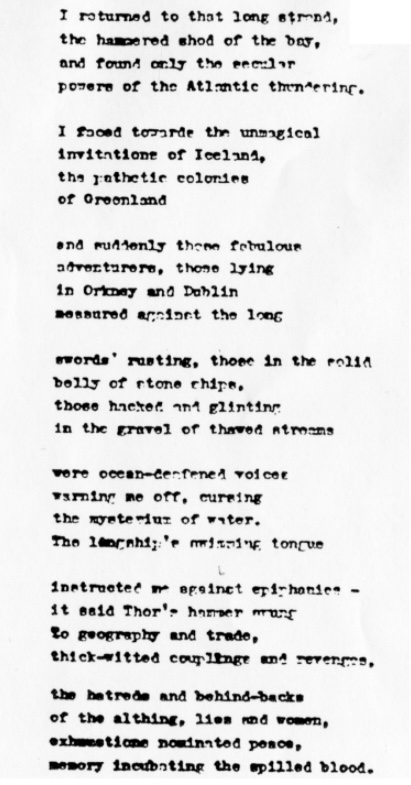

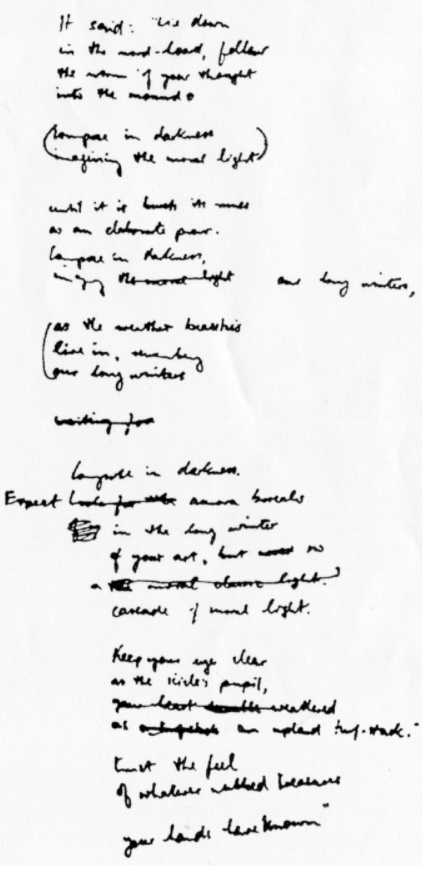

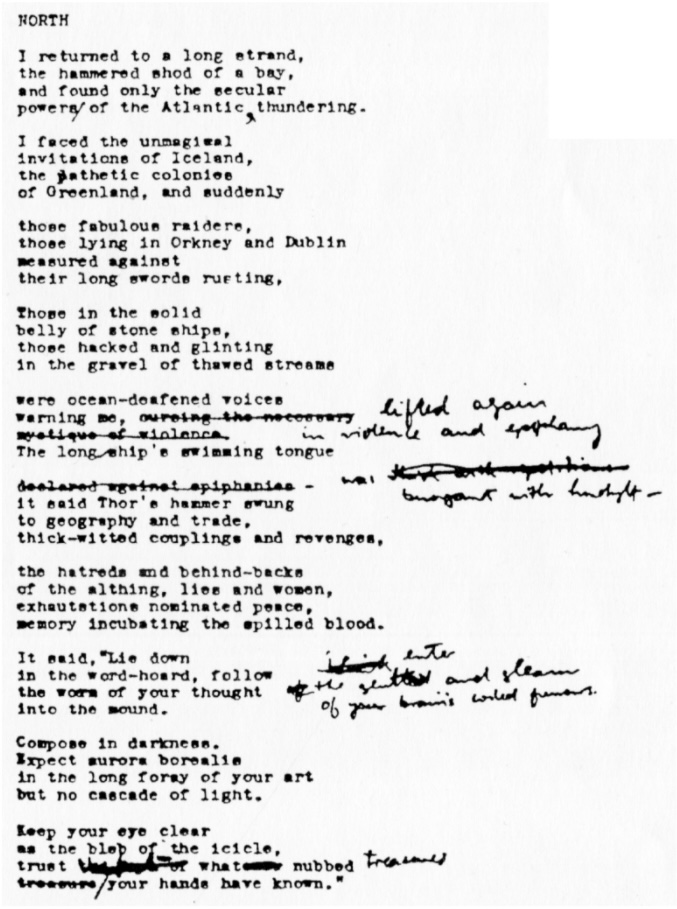

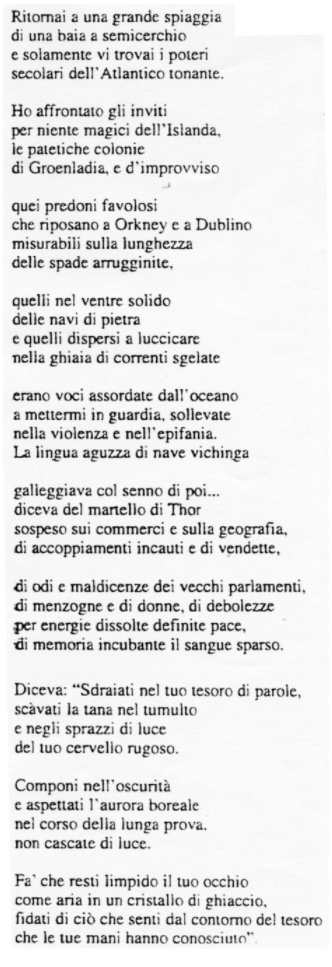

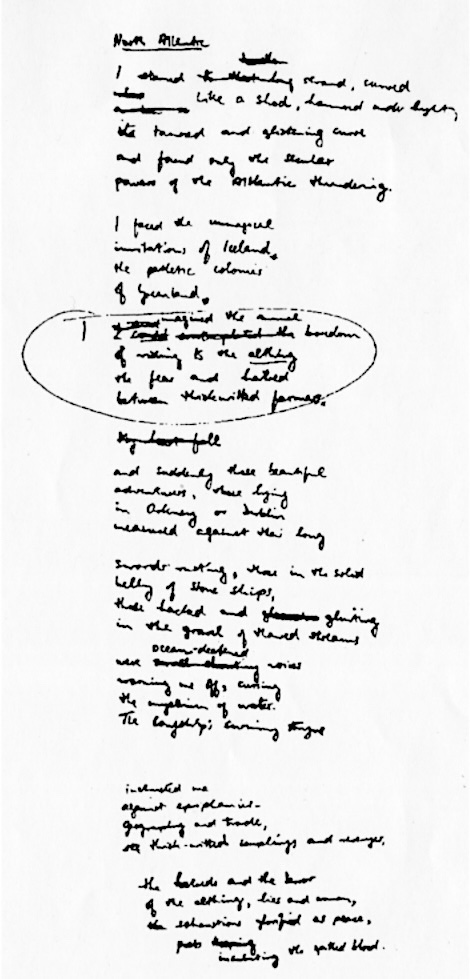

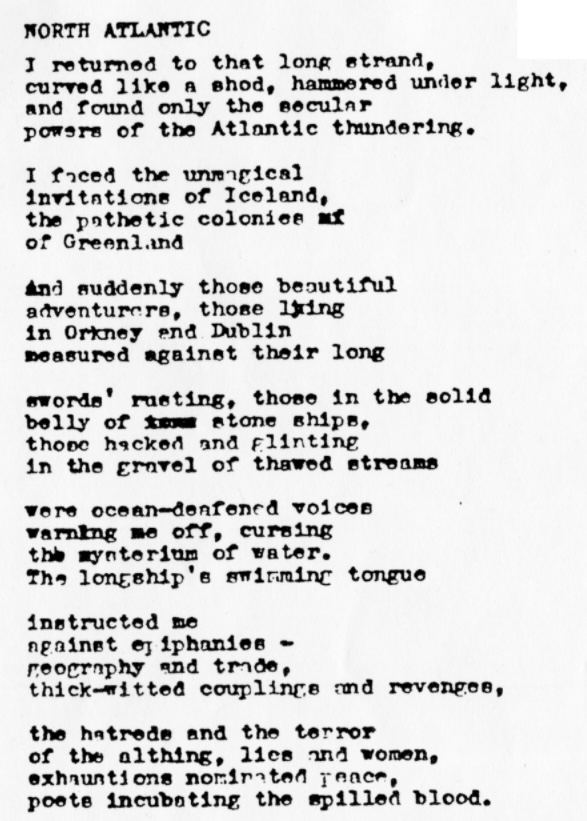

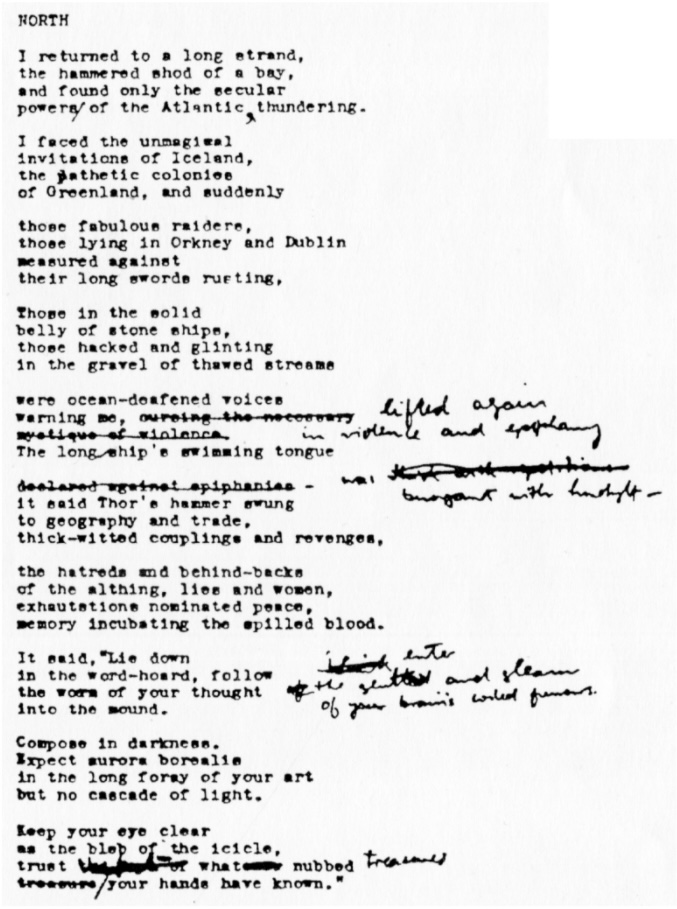

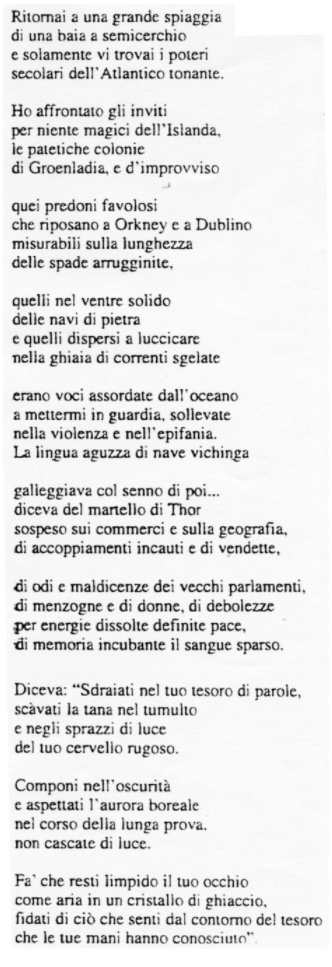

Gli otto documenti che qui pubblichiamo mostrano sei diverse e successive stesure di North, redatte da Seamus Heaney tra il 1974 e il 1975, nonché due mie traduzioni della stessa poesia.

Le due traduzioni sono state stese nel 1987 e nel 1995. Perché due versioni? Accadde che nel 1995 Heaney vinse il Premio Nobel. Io avevo già tradotto i suoi Collected Poems nel 1987, ma nessun editore italiano li aveva voluti: uscirono presso una fondazione privata, pur se prestigiosa, la Fondazione Piazzolla, solo nel 1991, a Roma. Poi ci fu la corsa alle traduzioni. Mi commissionarono di tradurre in brevissimo tempo una decina di testi di Heaney e fra questi c’era anche North. Non ero nella casa di città e non avevo la mia vecchia versione, inoltre nel 1987 avevo tradotto senza computer. Mi ritrovai quindi a tradurre una poesia che sapevo di avere già tradotto. Non diedi molta importanza alla cosa, pensai «verrà più o meno allo stesso modo». Fu solo in seguito – confrontando le due versioni – che mi resi conto dell’importanza del lavoro che nel frattempo avevo compiuto sugli avantesti. Ma mi resi conto anche d’altro, che racconterò in seguito.

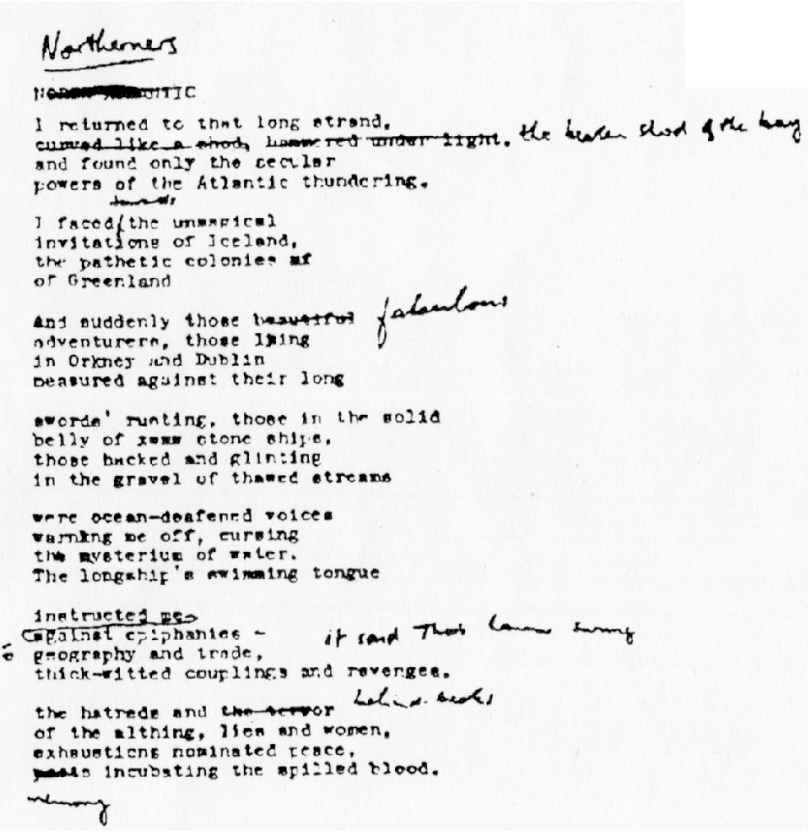

Con la sua Parker, Heaney scrisse North Atlantic. Già si nota come il titolo iniziale fosse diverso e come, prima di giungere a North, esso sia passato anche attraverso la fase Northerners. Quindi il titolo ha una germinazione interessante: North Atlantic connota qualcosa di geograficamente preciso, poi Northerners passa a indicare le popolazioni del Nord, trasformandosi infine in un più generico, quasi lontano e vitreo North. Così quella spiaggia che Heaney menziona al primo verso nelle stesure di North Atlantic e Northerners – «I returned to that long strand» – ricorrendo all’aggettivo dimostrativo «That», diventa in North – con un tono più distanziato e astratto, «I returned to a long strand». Anche la spiaggia diventa indeterminata.

Per limitare la nostra analisi ad alcuni snodi essenziali, consideriamo il verso conclusivo della prima stesura heaneyiana: «spilled blood», «sangue versato». Siamo nel 1973, in Irlanda imperversa la guerra civile; la poesia si conclude su un’immagine cruda e locale: incubavano – gli irlandesi – il sangue versato. Il sangue versato nei secoli dagli invasori vichinghi, angli, sassoni confluisce nel sangue versato dagli irlandesi contemporanei di Heaney. E sullo sfondo la torba, che conserva i cadaveri, in particolare quelli dei renitenti e delle vittime dei sacrifici.

Questo sangue versato, quindi, chiude il componimento nella prima stesura, laddove – al secondo verso della penultima lassa – «against epiphanies» pone al plurale un’entità dalla forte carica semantica, che nella versione definitiva diviene singolare, in perfetta sincronia con la distanza e la freddezza atemporale che l’autore riesce a fare acquisire al componimento.

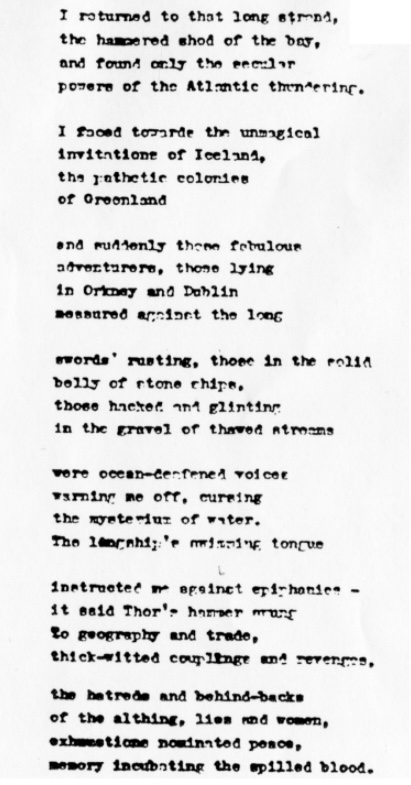

Heaney quindi ricopia, dattiloscrive, arrestandosi su «spilled blood»; e nella terza versione ci fornisce un indizio su ciò che il testo diverrà. Leggiamo un appunto scritto di nuovo a penna, una ‘correzione’, un «it said». Su di esso ruoterà poi tutta la poesia. Quell’«it» designa la lingua, con diretto riferimento all’ultimo verso della terz’ultima lassa nella seconda versione: «the long ship’s swimming tongue», la lingua nuotante della nave. È l’immagine della nave vichinga, strettissima e per questo veloce come una lingua di serpe saettante. Questa lingua – con un magistrale gioco polisemico – diventa la lingua che va stivata nelle navi, custodita come un tesoro e trasportata dall’Irlanda all’Islanda, alla Groenlandia a Terranova. Conserva, dice Heaney a quel marinaio, il tuo tesoro, le tue parole, le tue radici etimologiche.

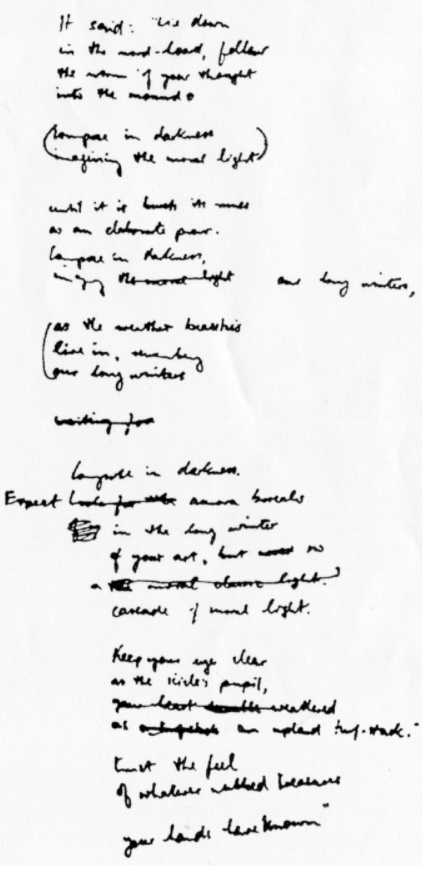

La poetica di Heaney da questo concetto trae grande nutrimento. «It said», essa – la lingua – disse «Thor’s hammer swung»: ricadeva il martello di Thor. Il miracolo di fusione, di inglobamento nel testo anche del concetto di lingua e di mitologia pagana avviene nella quarta stesura. Heaney ricopia il testo, arriva a «spilled blood» e con la sua Parker prosegue, perché «It said» della terza stesura gli dà lo slancio; su quell’«it» inizia la nuova lassa. Siamo al perno tonale del componimento, «it said: lie down». Come al cospetto di un motore che riparte, la quarta stesura, per metà dattiloscritta e per metà vergata a penna, ci illumina su come il testo sul termine ‘lingua’ sia cresciuto su se stesso. La lingua dà consiglio all’uomo. Come nel distico finale dell’Ode on a Grecian Urn di John Keats, l’entità astratta si fa voce.

Nelle stesure 5 e 6 Heaney ricopia nuovamente il testo con «epiphanies» – che poi finalmente diventa singolare nella stesura 6 – dove appare un’aggiunta a penna: «Hindsight». Il termine designa il concetto contrario rispetto a «foresight», il giudizio di previsione. Hindsight è il senno di poi, galleggiante come la nave ma col senno di poi, col senno della realtà di coloro che si scannano. Col senno di poi essi capiscono di aver sbagliato, ma nel frattempo hanno già allevato dei figli che a loro volta si scanneranno. Questo è il punto cruciale per Heaney. Vuole essere irlandese e vuole dare anche torto agli irlandesi.

Per quanto riguarda le mie due traduzioni, ritenevo sarebbero risultate molto simili. Non era stato un esperimento voluto e non pensavo che mi sarei messo in difficoltà da solo. Perché da traduttore posso anche permettermi di tradurre e basta, ma da traduttologo sono obbligato a darmi delle spiegazioni ai fenomeni del tradurre.

Esiste – è vero – una teoria scientificamente ineccepibile – che potremmo definire ‘neurologica’ – secondo la quale tali e tante sono le connessioni che il nostro cervello può mettere in atto quando traduciamo, da risultare praticamente impossibile – anche a distanza di breve tempo – la redazione di una traduzione identica da parte dello stesso traduttore. Per questo mi aspettavo di tradurre in modo solo simile, ma risolvendo gli snodi essenziali con cifra riconoscibile.

Invece, se considero i due versi iniziali – «I returned to a long strand» – scopro che nella traduzione dell’’87 li avevo sciolti nella sequenza dodecasillabo – novenario («Sono ritornato su una lunga spiaggia / l’ansa a gomito di una baia»), mentre nella traduzione del ’95 ricorro a due sonori ottonari: «Ritornai a una grande spiaggia / di una baia a semicerchio».

Se il fatto di avere analizzato nel frattempo gli avantesti, mi dava ragione di altre differenze (per esempio il verso decasillabico «La lingua nuotante della nave», della prima traduzione, diviene – grazie all’influenza dell’avantesto – un endecasillabo: «La lingua aguzza di nave vichinga»), proprio non riuscivo a capacitarmi della differenza di ritmo, di complessiva intonazione. Allora ritornai ai miei appunti teorici e approfondii la riflessione alla luce – nuovamente – del concetto di poetica.

La teoria della traduzione ci aiuta fondamentalmente a riflettere su ciò che abbiamo già compiuto nella pratica. Perché ancora non capivo le ragioni di quella radicale diversità di approccio? Perché non applicavo a me stesso fino in fondo le conseguenze della definizione anceschiana di poetica che tante volte avevo citato.“La riflessione che gli artisti e i poeti compiono sul proprio fare, indicandone i sistemi tecnici e le norme operative, le moralità e gli ideali è la poetica.”In particolare nel secondo gruppo di termini. Che cosa significano davvero ‘le moralità’ e ‘gli ideali’? Significano che un autore e/o traduttore si nutre non solo di cultura ma anche di ciò che gli sta attorno, della vita che conduce, dell’inflessione dialettale con cui gli si rivolgevano le persone care quando era bambino, del primo sapore del pane: tutto questo forma la nostra anima e resta il fondamento di quello che scriviamo, di quello che sentiamo. Ebbene quando mai – spontaneamente – si riesce a strappare a un lombardo un passato remoto? Io nell’87 insegnavo all’università di Bergamo e abitavo in provincia di Varese dove sono nato. Poi che cosa accadde? Vinsi una cattedra di prima fascia all’Università di Cassino e scesi ad abitare a Roma. L’uso del passato remoto divenne per me spontaneo, naturale. Ciò che stando a Bergamo o a Varese, mi sarebbe risultato indigeribile (l’attacco coi due ottonari al passato remoto) divenne per me accettabile, desiderabile. Mentre il passato prossimo della prima versione cominciò a suonarmi legnoso, prosastico.

Così oggi – mentre ribadisco la fondamentale importanza per il traduttore di accedere anche agli avantesti – non sono in grado di sostenere quale dei due ‘attacchi’ traduttivi sia migliore. In traduttologia non è possibile essere normativi. Non si può affermare: «qui si deve tradurre così», perché è la complessità dell’esperienza di un uomo, di un artista, di un traduttore che in toto risulta in gioco. L’importante è che – complessivamente – la traduzione che in quel particolare giorno si è compiuta sia coerente, risponda a un ritmo autentico, possegga una intonazione profonda. Esiste un momento nella storia del mondo esterno e un momento della storia personale di ciascuno di noi, che si sovrappongono, fino a coincidere: poi quel momento passa e si deve ricreare una nuova coincidenza. Questo è il flusso della vita e il tradurre nella sua accezione più ampia è il nostro vivere e quindi il nostro comunicare.

– – –

The myth of Babel tells of the loss of the earth’s one language and one speech, and the confusion of languages. Suddenly every object and every idea assumed a plurality of names, and the oversized tower, symbol of human imagination and hubris, was abandoned within the shadow foreboding its destruction. With an unprecedented series of correlated texts, Specimen explores these magnificent ruins, hearing echoes of the multiplicity of languages and the birth of translation. This collection includes texts about Babel, translation or language, and special translations. In September 2021, 20 years after 9/11, the Babel festival will focus on the multiplication of languages and the present diaspora from the regions of ancient Babylon – the scattering of the children of men over the face of all the earth. >> www.babelfestival.com

Published August 14, 2021

© Franco Buffoni

The Central Role of the Concept of Rhythm

Written in Italian by Franco Buffoni

| A specimen of Babel: Stories on the loss of the earth’s one speech and the confusion of languages

Translated into English by Richard Dixon

An original poem is not a poem that speaks about things that no one has ever spoken about before. Leopardi is unique when he speaks about/to the moon, not because the subject is original (we find it even in the letters that Pietro Colletta writes to him), but because his poetry is highly vibrant and dynamic. When Keats, in the final couplet of Ode on a Grecian Urn, associates Beauty to Truth and Truth to Beauty, he is not making an original association: they are two words frequently linked together in English eighteenth-century aesthetics. But Keats restlessly revives that association within his poetry. And those lines, once read, are not forgotten.

This happens because poetry is a language: a language different from the one we use in everyday communication, and far richer, more complete, more fully human. “A language,” in the words of Giovanni Raboni, that is “at the same time carefully premeditated and deeply involuntary, capable of connecting things that are seen and things that are not seen, of relating together what we know with what we don’t know.”

I have translated much in my life, and have become increasingly convinced that the real difference is not between prose and poetry, but between writing that contains an internal rhythm of its own and writing that doesn’t have it.

The Venerable Bede made a very clear distinction. “Rhythm can exist in itself without metre; whereas metre cannot exist without rhythm. Metre is a song constrained by a certain cage; rhythm is a song without rational measures.”

We find this distinction expressed more recently in Traité du rythme by Henri Meschonnic and Gérard Dessons: “Rhythm is not formalistic, in the sense that it is not an empty form, a schematic whole that one would show or not show, according to mood. The rhythm of a text is its fundamental element, because the rhythm operates the synthesis of the syntax, the prosody and the different enunciative movements of the text.”

With poets (though I use the word, like Luciano AnceschiAutonomia ed eteronomia dell’arte: sviluppo e teoria di un problema estetico (Sansoni: Florence, 1936)], in a broad sense: it would be better to say “with artists”) what counts with rhythm is that moment when it becomes words, namely written language, and is therefore achieved through a particular intonation. (Since rhythm is subject, if a poet finds the rhythm, they find the subject; if they don’t find it, the lines they are writing are not art).

The rhythm is therefore this breath within the writing, which includes all meters. Since meters are a historic fact, they can change, they are basically linked to fashion, in the sense in which Giacomo Leopardi used it. Whereas rhythm is ancestral: it is that breath that comes from learning to speak, from the maternal heartbeat.

It is certainly no coincidence that Meschonnic, in this respect, quotes examples both from literature and from the figurative arts. In this latter case, it is enough to replace “word” with the terms such as “brushstroke”, “image” or “portrayal”. The difference isn’t therefore between abstract painting and figurative painting, but between a painting (abstract or figurative) that contains its own intrinsic rhythm, its own measure, and a painting (abstract or figurative) that doesn’t. The latter is not art. That’s all there is to it.

Clearly, the difficulties that I encounter when it comes to translating The Four Quartets are of the same general nature as those I encounter when translating The Waves, even if to the untutored eye T. S. Eliot has written in poetry and Virginia Woolf in prose.

Drawing upon a celebrated reflection by Mikhail Bakhtin on translation as a dialogic relationship between two artistic entities – a relationship which becomes no longer “of rank, but of time” – the operation is concerned with the movement of language and time of reception not only in the target language, but also in the source language. This encounter-confrontation unearths a difference and therefore also updates the source text.

Briefly, we could start off with the question of retranslation: why do we accept the notion that it is “permissible” to retranslate? Because we feel that every generation ought to have its own Goethe, its own Dante, its own Shakespeare that can speak in the literary language of that generation. I translated Keats in 1980, my translation is still in circulation, but I am sure that another poet (or I myself) will retranslate Keats into Italian in the next few years and will republish it. Why do we take it for granted that this is “permissible”? Because we take it for granted that language moves in time, that our own language is constantly changing. And the transition we make with the concept of Sprachbewegung aims to include in this language-movement also the text written in the source language. That ancient or modern classic that we set about translating is itself therefore also moved in time.

Not only does the target language “become” – an obvious consideration since the time of Wilhelm von Humboldt – but so also does the source language “become”, because over decades, over centuries, the structures that comprise that text – syntactical structure, grammatical structure, semantic values, pronunciation – have gradually altered. How can it be thought that this text has remained the same? And this is where the concept of translation as a “poietic” encounter – as an encounter of poetics – comes in. If translating literature brings about an encounter between the poetics of the translator and the poetics of the translated text, this encounter – which occurs at point x in time and space – is unique and unrepeatable, because the state of the two works and of the two languages that are brought together at that moment is unique and unrepeatable.

The same translator, even over a short space of time, translates in a different way. This, it so happens, is an experience that I myself had when I retranslated Seamus Heaney without checking the translations that I had made ten years earlier. The poietic encounter between source text and target text are like two arrows that intersect – and only in that exact moment do they intersect in that way. In another moment – before or after – the two arrows (the two texts) would intersect in a different way.

By formulating our theoretical reflection in this way, we have linked the concept of movement of language in time with the concept of poetics. But here, knocking at the door, is also the concept of intertextuality: it completes the list of five fundamental points (all mutually connectable: poetics, rhythm, intertextuality, earlier drafts, movement of language in time) which enable our reflection to leave the field of dichotomic notions: ut orator/ut interpres; traductions des poètes/traduction des professeurs; faithful to the letter/faithful to the spirit; and so on.

To conclude by returning to the concept of rhythm, the current state of research would suggest three fundamental directions for “rhythmology”: a philosophical direction, a philological-linguistical direction, and a poetical direction.

In the first area we include philosophers, who should concern themselves basically with the category of rhythmicity in a broad sense, studying the function that rhythm has in the world.

In the second area we include philologists, who examine rhythm, trying above all to describe what it is (and here the prime auctoritas is that of the Venerable Bede). The task of philologists is therefore to agree on meaning, study the word, and lastly conduct their analysis using methods that consider the language and the history of language.

With poets – as we have said – what counts about rhythm is the moment in which it is turned into words.

What is common to all three areas is the study of how rhythm orders – and shapes – thought.

Whether we are discussing literary rhythm or musical rhythm or natural rhythms (tides, etc.), we start from a concept of measure, repetition, continuity, discontinuity, cadence. A heartbeat, therefore, as the highest example of something alien to the need for man to be a part of history, far more bestial and profound, ineluctable and ancestral, like the expansion and implosion of the universe, like primordial breath.

This would seem to be the line of definition preferred by poets. Rhythm as a vibration that crosses the world and, to varying degrees the human body, interpreted as a sensor that perceives and recognizes waves that have a corporeal nature. A rhythm, therefore, that is extraneous to poetic subjectivity, which flows and passes into the world, encountering nature and people.

On the other hand, if we agree on the fact that prosody and cadence are mechanisms through which children gain access to language, the poet – in their poièin – can only mirror this primary acquisition of language. From this point of view, we are born as poets, insofar as music is in the soul. And rhythm crosses the world, it is translated into the body and through this it is restored to the world: a process which today can be “disturbed” by the mechanical sounds of modernity.

Viewed in this way, clearly, the historical difference between prose and poetry completely collapses. The true difference is between writing that contains its own breath (its own rhythm) and writing that doesn’t. Then, whether the line stops before it reaches the end of the page, or whether it is written using one of the many metrical constraints that characterized poetical writing in different periods and languages, becomes a factor of no particular relevance.

* * *

The eight documents published here show six different and successive drafts of North, written by Seamus Heaney between 1974 and 1975, as well as two translations by me of the same poem.

The two translations were done in 1987 and 1995. Why two versions? Heaney won the Nobel Prize in 1995. I had already translated his Collected Poems in 1987 but no Italian publisher had wanted them: they were eventually published by a private although prestigious institution, the Fondazione Piazzolla, in Rome in 1991. There was then a rush for translations. I was commissioned to translate a dozen or so texts by Heaney, including North, in very little time. I was not at my home in the city and didn’t have my old version. Moreover, in 1987 I did my translations without a computer. I therefore found myself translating a poem which I knew I had already translated. I didn’t attach much importance to the matter: “it will come out more or less the same,” I thought. Only later – when comparing the two versions – did I realize the importance of work that I had done in the meantime on the earlier drafts. But I also realized something else, which I will explain later.

With his Parker pen, Heaney wrote North Atlantic. It is already noticeable that the initial title was different and how, before arriving at North, it passed through the Northerners stage. The title therefore has an interesting germination: North Atlantic suggests some precise geographical location, then Northerners moves toward indicating the populations of the North, being finally transformed into a more generic, almost distant and vitreous North. So the beach that Heaney mentions in the first line of the drafts of North Atlantic and Northerners – “I returned to that long strand” – using the demonstrative adjective “that”, has a more distanced and abstract tone in North, becoming “I returned to a long strand.” The beach also becomes indeterminate.

In order to limit our study to a few essential points, let us look at the last line of Heaney’s first draft: “spilled blood”. We are in 1973, civil war is raging in Ireland; the poem ends with a crude local image: they – the Irish – were incubating spilled blood. The blood spilled over the centuries by invading Vikings, Angles, Saxons merges with the blood spilled by Heaney’s Irish contemporaries. And in the background the peat, which preserves the corpses, in particular those who refuse to fight and the victims of sacrifices.

This spilled blood therefore ends the composition in the first draft, where – in the second line of the penultimate stanza – “against epiphanies” places a notion of strong semantic weight in the plural, which in the final version becomes singular, in perfect synchrony with the distance and timeless coldness that the author manages to confer on the composition.

Heaney therefore recopies, by typewriter, ending on “spilled blood”; and in the third version he gives a clue about what the text will become. We read a note, written once again in pen, a ‘correction’, an “it said”. Around this the whole poem will then revolve. That “it” refers to the tongue, with direct reference to the last line of the antepenultimate stanza in the second version: “the long ship’s swimming tongue”. It is the image of the Viking ship, very narrow and for this reason as fast as a darting snake’s tongue. This tongue – with a masterful polysemic effect – becomes the tongue/language that is loaded into the ships, guarded like a treasure and transported from Ireland to Iceland, to Greenland to Newfoundland. Conserve your treasure, your words, your etymological roots, Heaney tells that sailor.

Heaney’s poetry is greatly nourished by this concept. “It said”, this – the tongue – said “Thor’s hammer swung”. The miracle of fusing, of incorporating into the text also the concept of language and pagan mythology occurs in the fourth draft. Heaney recopies the text, reaches “spilled blood” and carries on with his Parker pen, because “It said” of the third draft gives him the impetus; on that “it” he starts the new stanza. We are at the tonal pivot of the composition, “it said: lie down”. As in the presence of an engine that restarts, the fourth draft, half typewritten and half handwritten, shows us how the text has expanded over the word ‘tongue’. The tongue gives advice to man. As in the last couplet of John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, the abstract entity speaks.

In the fifth and sixth drafts, Heaney recopies the text once again with “epiphanies” – which then finally becomes singular in draft six – where the word “hindsight” is added in pen. With hindsight they understand they have done wrong but, in the meantime, they have already brought up sons who in turn will fight each other. This is the crucial point for Heaney. He wants to be Irish and he also wants to criticise the Irish.

So far as my two translations are concerned, I thought they would turn out very similar. It wasn’t an intentional experiment and I didn’t expect to create difficulties for myself. For as a translator I can allow myself simply to do the job of translating, but as a translatologist I am obliged to study and explain translation phenomena.

True, there is an unimpeachable scientific theory – which we might describe as ‘neurological’ – according to which there are so many connections that our brain can make when we translate that it is practically impossible – even after a short space of time – for the same translator to produce an identical translation. I expected, for this reason, to translate in a way that was only similar, but to have resolved the essential points in a recognizable manner.

And yet, when I read the first two lines – “I returned to a long strand” – I found that in the 1987 translation I had turned them into a twelve-nine syllable sequence (“Sono ritornato su una lunga spiaggia / l’ansa a gomito di una baia”), whereas in the 1995 translation I used two resonant octosyllables: “Ritornai a una grande spiaggia / di una baia a semicerchio”.

While the fact of having meanwhile studied the previous drafts justified other differences (for example, the ten-syllable line “La lingua nuotante della nave” of the first translation becomes – thanks to the influence of the previous drafts – a hendecasyllable: “La lingua aguzza di nave vichinga”), I couldn’t understand the difference of rhythm, of overall intonation. I then returned to my study notes and gave it further thought, once again from the poetical point of view.

Translation theory basically helps us to think about what we have already done in practice. Why did I still not understand the reasons for that radical diversity of approach? Because I was not applying to my own work the consequences of Anceschi’s definition of poetics that I had quoted so many times.“Poetics is the reflection that artists and poets make about their work, indicating technical systems and operative norms, moralities and ideals.” In particular, in the second group of terms. What do ‘moralities’ and ‘ideals’ really mean? They mean that authors and/or translators are nourished not only on culture but also on what there is around them, on the life they lead, on the voices and accents of loved ones who talk to them during their childhood, the first taste of bread: all of this is what forms our spirit, and it remains the basis of what we write, of what we feel. In Lombardy does anyone ever – spontaneously – use the past historic? No. I was born there and taught there, at the University of Bergamo. Then, in 1987, what happened? I was appointed professor at the University of Cassino, in Lazio, and went down to live in Rome. It became natural, spontaneous, for me to use the past historic. What I would have regarded as unpalatable while I was living at Bergamo or Varese (to start with two octosyllables in the past historic), I then felt to be admissible, even desirable. Whereas the simple past in the first version began to sound wooden, prosaic.

So today – while I stress the fundamental importance for the translator also to have access to previous drafts – I cannot say which of the beginnings in the two translations is better. In translatology one cannot set down firm rules. One cannot say: “here you have to translate like this”, because it is the complexity of experience – in toto – of a person, of an artist, of a translator that comes into play. Most important is that, overall, the translation done on that particular day is consistent, responds to a genuine rhythm, contains a depth of intonation. There is a moment in the history of the outside world and a moment in the personal history of each one of us when the two overlap and correspondence: that moment then passes and a new correspondence has to be recreated. This is the flow of life, and translation in its widest sense is our experience and therefore our way of communicating.

– – –

The myth of Babel tells of the loss of the earth’s one language and one speech, and the confusion of languages. Suddenly every object and every idea assumed a plurality of names, and the oversized tower, symbol of human imagination and hubris, was abandoned within the shadow foreboding its destruction. With an unprecedented series of correlated texts, Specimen explores these magnificent ruins, hearing echoes of the multiplicity of languages and the birth of translation. This collection includes texts about Babel, translation or language, and special translations. In September 2021, 20 years after 9/11, the Babel festival will focus on the multiplication of languages and the present diaspora from the regions of ancient Babylon – the scattering of the children of men over the face of all the earth. >> www.babelfestival.com

Published August 14, 2021

© Franco Buffoni

© Specimen

Other

Languages

Your

Tools